I Don’t Know If I Am Real Without You

Stabbing Westward & Goth Confusion

by kristine langley mahler

I didn’t know what I wanted until I was looking at it. I’d never seen a boy bending gender into black eyeliner hoops around his eyes, unruly dark hair curtaining the corners of his cheekbones, emotion and ennui dueling for attention as he slouched in an anachronistic black fabric—snakeskin, velvet, leather. I was immediately attracted to the unfamiliarity of a beckoning sadness. I shut the magazine cover and lifted my sixteen-year-old head: I was going to find me a real-life goth.

What I got was a half-sheet flier to “Goth Night” in The Cathedral, eleven Hautians (as we from Terre Haute self-loathingly-identified ourselves, as in, "God, cruising the 'Bash is so HAUTIAN, I don't know why anyone still does it") moping around a half-renovated room carved off the Indiana Theatre, a CD on a sound system hooked up to the speakers some hopeful employee had bought to entice a real band to detour off 70 on their way to Indy; everyone knew better.

In the rural Midwest of the late 90s, there was no way to distinguish Real Goth, no snarky child-critics ready to sneerily define the minute differences between x and x because the internet didn’t do that then. How can I take you back to the baby internet days? How can I remind you of the search engines—Lycos, Excite, Ask Jeeves—and how little we could know? “Industrial” referred to the Columbia House plant up on Fruitridge Avenue, or the shabby businesses near the wastewater plant that we all called “Over by The Smell”—a location everyone in town knew and avoided. Industrial wasn’t a sound unless it was the sound of the chains locking the Pfizer plant shut for good.

We didn’t know the difference. There was no one to call the kids lounging by the (let’s all say it together) theater classroom “mallgoths”—our mall serviced the surrounding farm towns, and we were an hour away from the real shopping at Circle Center’s Old Navy or Victoria’s Secret. When Hot Topic opened, it made no sense to our regional demographic—it was a crazy aberration, a mistaken movement. My best friend and I would sit at Cinnabon, directly across from Hot Topic, and watch people try to get up the courage to enter beneath those storefront gates. The slowed approach, the shoulders turning slightly toward the entrance, the oh-I’m-going-to-sit-on-this-bench-and-rummage-through-my-purse-while-I-scope-out-the-customers-inside. Everything was on fire in Hot Topic: flame wallets with chains, etched flame rings, flame boxers. I’d walked in without missing a beat and bought shoelaces printed with little flames; I stitched the shoelaces along the outer seams of my hunter-green corduroy cut-offs like stripes.

The minister of the local nondenominational church had picketed the opening of the Honey Creek Mall Hot Topic. Wasn’t that proof Hot Topic was the lair of Real Goth? Hot Topic seemed to brandish the right sartorial affectations: a lot of black clothes, lace-up mid-calf boots, silver jewelry over gold. A convincing appearance, interleafed with the right band names to mention—the ghoulish corpse with nine inch nails, the screen siren juxtaposed with a serial killer—projected an authenticity I didn’t question.

So when this boy I’d been talking to on the internet announced that he liked some band called “Stabbing Westward,” I was sure they must be goth.

When I’m interested in a band now, I watch their videos on YouTube, I read their Wikipedia articles, I Google their names. In 1998, I had to sneak access to MTV and hope their videos were played between the time I got home from school and before my parents got back from work. I saw a lot of “Closing Time and “The Boy is Mine,” but not what I was looking for.

I have to reconstruct Stabbing Westward from the back to the front, filling in what I didn’t know at the time with what I know now. I can parrot Wikipedia, I can read concert reviews. I can link up the music videos I never saw before YouTube. I can research all night. I can deep-dive into band interviews and collate their whole history, but who they were is not going to tell you who I thought they were.

Christopher Hall and Walter Flakus met in 1986 in Macomb, Illinois, at Western Illinois University—a little state school west of Peoria and south of Galesburg. Christopher Hall reportedly said, in an interview missing its Wikipedia permalink,

Since we went to Western Illinois University, [the band name] Stabbing Westward had a certain 'kill everybody in the school' vibe to it! The school's way out in farm country and the country is really close minded. I was walking around like Robert Smith with real big hair, big baggy black clothes, black fingernail polish and eye makeup. They just didn't get it. We hated the town.”

After being misidentified as a Chicagoan, Hall clarified,

Actually, we're Illinois boys. Walter and I are from the Peoria zone, down in the middle of Illinois, right in the buckle of the Bible Belt.”

I’d always thought the Bible Belt swung across the beer belly of the South, but I knew what Christopher Hall meant. I didn’t know Macomb but I knew Macomb, a town on the western border of another flat I-state, an irrelevant river nearby. I knew what it was like to explain my home by situating it in reference to the nearest big city.

So I wasn’t surprised to learn that Hall and Flakus eventually moved to Chicago, the only Midwestern city with any cred outside of the region. They added a drummer (Chris Vrenna, later traded for David Suycott) and two guitarists (Stuart Zechman and Jim Sellers) and Stabbing Westward’s first album, Ungod, was released in 1994. Hall described the album, in 2008, as “the darkest album we made, the angriest record…it was like, on scale with Nine Inch Nails.” The surviving music videos from Ungod corroborate:

“Lies,” where the band is literally in a dungeon:

(You! Are haunting my reality! Now every time I think about you I DIE!)

“Nothing,” with the requisite maggots and tarantula, plus the band in full half-shadow:

(I don’t want it! I don’t need it! BUT I CAN’T STOP MYSELF!)

But I can’t really dissect Ungod because I didn’t listen to Ungod at all. I’d never heard a single song from that album before writing this essay. In 1998, because I wanted that boy from the internet to like me, I went to Penny Lane and bought someone’s exchanged advance copy of Wither Blister Burn & Peel, Stabbing Westward’s second album, for seven or eight bucks, so this was the cover I knew:

Christopher Hall in a white cardigan, arms like Jesus, Walter Flakus-Jim Sellers-Andy Kubiszewski (the new drummer) in baggy black shirts, hands in their pockets, a bad photo edit under Chris’s left armpit where someone’s black shirt had been Photoshopped in, or out. Was that a thing in 1995?

I only liked six of the ten songs on Wither Blister: I hated the donkey-bray of “I Don’t Believe” and “Crushing Me.” “Slipping Away” was annoying, and “Sleep” made me so uncomfortable I would panic if I missed the tell-tale hammer at the beginning; a man whispering his appropriation of a girl’s sexual abuse narrative creeped me out.

“What Do I Have to Do?” was the first single and the first big hit for Stabbing Westward, climbing to #60 on the Billboard Hot 100 (an all-time high for the band); it’s a wondrously confused teenage claim, pleading for answers while simultaneously admitting “I know exactly what you’re thinking.”

The video for “Shame,” the second single, is essentially a videographic representation of The Rembrandts’ “April 29”—a guy gets out of a mental institution and comes creeping after his ex. The music video is a horror movie with porous boundaries—the band is both in the movie and watching the movie—but Christopher Hall is oblivious, so intent on expressing his pain that he doesn’t notice everyone in the room leaving him, person by person.

I’d argue that the lyrics to “Shame” are terrifically gothic in their existentialism—I don’t know if I am real without you; what is left for me without you? I don’t know what’s real without you; how can I exist without you?—but Stabbing Westward never claimed to be goth. That collection of Midwestern boys in black clothing with black hair, releasing Ungod, Wither Blister Burn & Peel, Darkest Days—they never said they were goth. Can you blame me for misinterpreting?

Stabbing Westward’s third album, Darkest Days, was released on April 7th, 1998. The next day—my best friend’s sixteenth birthday—we drove an hour and a half northwest to Champaign to meet the two boys we’d been emailing. No, we didn’t listen to a copy of Darkest Days. We didn’t know about Darkest Days yet. We didn’t know that we would shape ourselves into upside-down cross-shaped vessels to impress boys we didn’t yet know were fake goths, wearing the rune necklaces and black velvet shirts their moms had bought for them at Lix, the goth store in downtown Champaign. We didn’t know we were only attracted to the paint of danger—their black nails, their boy-eyeliner—they were Catholic boys in a central Illinois town, tracing the toes of their black boots around the edges of gothicism.

We didn’t know my best friend would not succeed in turning her internet boy-friend into a real internet boyfriend, but I would.

The fake goth boys from Champaign convinced one of their mothers to drive them to our town seven months later, where (for reasons far too elaborate and stupid to go into) we enacted a fake wedding between me and my internet not-yet-boyfriend, complete with about fifteen witnesses, a prearranged duel, and, shamefully, a fake kiss. He wore a black snakeskin shirt and black corduroys and I wore a prairie-style vintage wedding dress I’d gotten at Goodwill, and in the thick dark of two a.m., we both had our real first kiss. I was head-over-fucked-up in love and I fell into my internet boyfriend in the following months, decked out like a Halloween doll in the dress he’d bought me to wear to his school’s Valentine’s Day dance.

He was into Darkest Days? On my way to F.Y.E. to buy it. I didn’t know Darkest Days was an album about a dying relationship. I didn’t learn that until Wikipedia taught it to me in the 20-teens, too late for us both.

Darkest Days is a concept album consisting of four acts, with each portraying a different emotional phase gone through after a break-up. The first act (Tracks 1-4) is about sabotaging the relationship. The second act (Tracks 5-9) is about lust, hope, and longing. The third act (Tracks 10-12) is about hitting rock bottom after it is all over. The fourth act (Tracks 13-16) is about recovery and self-respect.

I sabotaged my relationship, sending passive-aggressive email reminders of our month-anniversaries, petulantly dissatisfied with his apologies. I spent hours lost in lust, longing to be closer to my internet boyfriend, re-inscribing every time he’d touched my hip, wondering if he would return the favor if I reached beneath his shirt.

Darkest Days was littered with hits—the video for “Sometimes It Hurts” displayed Christopher Hall, with Hot Topic Manic-Panicked purple hair, wandering through a dream sequence paying homage to The Wizard of Oz. There are politically-incorrect Munchkins in construction gear, more dress-worship (harkening back to Stabbing Westward’s “Nothing” video), and a derelict house in the middle of a field being torn down, evoking a pathos that only a rural Midwesterner can really understand.

The bigger hit from Darkest Days, “Save Yourself,” was featured on a handful of movie trailers. The video features a classic 90s “random body parts and freaks” presentation in yellow-green light, the band in leather (pleather?) pants and black long-sleeved shirts.

The third single, “Haunting Me,” didn’t get a video, but I could have directed one: a stack of printed emails from my internet boyfriend, his missives growing increasingly shorter as I incessantly reread them, looking for hidden messages in the specific lyrics from Darkest Days that he chose to title his emails; how he left out the words that would have made my tongue touch my teeth, “I miss, God I miss…you,” the ellipses omitting the truth—he had never woken up beside me.

Tell me I wasn’t a Real Goth, navy blue eyeshadow swabbed on my eyelids and liquid eyeliner rimming my closed eyes, holstered into a gunmetal-gray prom dress, clinging to my internet boyfriend in his empty house six months after we’d first kissed, the three quiet, dark, throbbing, minor-chorded songs (Tracks 10-12! “Hitting rock bottom after it is all over!”) orchestrated by my internet boyfriend as the background to our feverish kissing.

He forgot to jump up and turn the CD off as the outro for the whispered hurt of “Goodbye” was ending, so we got blasted with the horribly loud discordance of “When I’m Dead,” shattering the mood and getting us out the door.

It should surprise no one that my internet boyfriend broke up with me a month and a half later. When I had occasion to return to his town, I went to Hot Topic first and bought a sweater I thought he’d like—a fuzzy dark gray sweater with thumb-holed sleeves I could pull over my hands. Maybe he did like it; for years afterwards he kept emailing me, refusing to pull out the power cord. Maybe I liked the suggestion of a gothic haunting-for-eternity more than the truth of its lingering stagnation.

I never made it through the fourth act; I kept breaking all the promises that I kept making to myself. I would swear it was over—my internet ex-boyfriend was a fraud who had insinuated himself into the darkly appealing sex-pull of goth, that erotic neck-biting underworld of submission, but he’d never even tried to touch my bare skin—and then I would email him back, every time, wanting to transform him.

Fauxgoth. Softgoth. Mallgoth. Is it real to call sadness fake? Was there a teen who wasn’t goth-sad, drawing black zeroes around their eyes? I forewent the black lipstick to color my lips red, mimicking the kind of mouth you’d find on a grown woman, an affectation of how I wanted to be seen.

I skipped class in high school once, but I didn’t know what to do with my freedom—I had faked a dentist appointment to prove a point, that I could do something wrong. Like any good suburban girl, I got in my Ford Taurus and drove to the mall—but I went to Hot Topic. I bought a pair of fishnet sleeves and I made it back to fourth period on time, ostentatiously stashing the bag in my locker, hoping someone would notice and think Wow, I didn’t know she skipped class; I didn’t know she actually bought things at Hot Topic.

I cut the sleeves off a long-sleeved black velvet shirt and reattached them with safety pins.

Was I supposed to know better? How could I? When I had tried to search “how to dress goth,” I got an Angelfire website where a kind old goth instructed me on how to sew my own cape.

I had saved an application to work at Hot Topic, my information filled out, waiting to turn it in on the day I turned 18. Instead, my summer job after senior year was the front desk clerk at Sylvan Learning Center, taking payments from moms and dads, wearing the Old Navy button-down shirt I’d acquired at Circle Center, driving home along the backroads so I could scream with the Darkest Days CD I kept jammed in my Taurus.

I moved to another Midwestern I-state for college and played Stabbing Westward on the radio station where I deejayed from 4-7am every Wednesday. I sent those songs to my internet ex-boyfriend, imagining him listening out there on the windswept prairie back in his I-state, the radio waves crashing over the roar of I-74 to remind him that sometimes it hurts so much to lose the one you love.

I would ritually cue up my car stereo to play Darkest Days as I drove home from college on breaks, past the exits for Champaign. If I could allow myself that ten-minute indulgence, I hoped I could resist the urge to email him back. I guess I thought the repetition of listening to those trips back in time would grind down the old emotion, give me perspective, make it seem maudlin.

I have been calling him my “internet boyfriend.” But he was my only boyfriend in high school, and I maximized our relationship into a drama which sustained me until I got another boyfriend two years after we broke up.

I said it sustained me until I got another boyfriend two years after we broke up. But the drama sustained me for decades because he was the only boy who had dressed me into the girl I’d wanted to be.

Stabbing Westward’s fourth and final album, Stabbing Westward, was released in the late spring of 2001, my first year in college. I didn’t know why the album was self-titled—who self-titles their fourth album?—but I loved the album cover, a gorgeous shirtless goth girl with smeared black eye makeup and bitten red lips looking up at the camera making a pre-MySpace face. I could cover that look, I thought to myself.

The album also opened decently, at last,—no “I’m such an asshole, God I’m such a stain” (Wither Blister) or “My RAGE! My PAIN!” (Darkest Days). Instead, Christopher Hall sang, “Each night I feel the distance that has grown between us open up as lonely as the space between the stars,” because of course Stabbing Westward pulled through with a song all about me and my internet ex-boyfriend. But as “So Far Away” ended and the next song began, I cringed at the audible acoustic guitar, my conflicting horror and gratitude growing by the third, “I Still Remember,” as Christopher Hall actually crooned the line “Now I don’t even recognize the girl I swore that someday I would ma-a-arry.”

How dare he talk about marriage? Why wasn’t he screaming, in some new phraseology, “If I can’t make you want me, WHAT DO I HAVE TO DO?” Where was the man who had once written an entire song compelling a girl’s acquiescence by describing what he would do once he was inside her? Even more horrifying than this smooshy betrayal of Stabbing Westward’s rough lust was my attraction to the song—I was an obsessive nostalgic. The male narrator in “I Still Remember” was, finally, remembering something a girl like me might have forgotten—and begging me to remember.

If Christopher Hall could soften like this, if the band could hold the dueling personas of a crawling goth sex-queen and an emotional rock plea within the same album, maybe the space between who I was and who I wanted to be could collapse and press together.

But they didn’t, not for me, not for Stabbing Westward. At the time in 2001, Christopher Hall explained away the band’s new direction,

Every time we titled an album the title seemed to get darker and darker. I mean, we started with "Ungod," went to "Wither, Blister, Burn and Peel," and then we went to "Darkest Days." Every time someone would pick up one of our records in the store, they'd look at this picture on the cover, which is generally pretty dark, then they'd see this name "Stabbing Westward," which is a pretty violent sounding name. Then they'd read the title, and they'd make all these assumptions before they even went to the listening booth. A lot of the things we write about are kind of love songs and stuff like that. It's not like it's Satan worshipping.”

The interviewer confronted Christopher Hall over that contradiction,

But your new album cover seems to go against that idea. Although it's simply titled "Stabbing Westward," you've got this goth girl with smeared makeup who looks like she wants it...

Christopher:

Or getting it! (laughs) Yeah, you're right, the cover is still dark…I think the intent was to be more sexy than violent, though.”

But the bound body on the back of this jokey-ass, fake goth record tracked with lyrics like “I’ve never been loved by an angel until tonight when your heaven filled my world” was a contradictory fucking mess. The album did poorly (no surprise), but I didn’t notice because I rarely listened to the self-titled album at all, still holed up in my preferred Darkest Days cavern. I met a boy in college who only knew of Stabbing Westward from the Wesley Willis song “Stabbing Westward” (for the record: Stuart Zechman, the only band member called out by name in Willis’s song—“Stuart Zechman owes Tammy Smith $250”—still declares “I never owed [her] a dime”). After we’d been dating for three weeks, the new boy bought an excessively expensive pair of black wings from Hot Topic to wear to my Halloween party. I wore my fake wedding dress again, pretending to be an “angel.”

In the years after their 2002 break-up, nine months after the release of the self-titled album, Stabbing Westward became my mnemonic for the goth culture in which I had dabbled, the Midwestern Hot Topic edginess which had seemed so sharp, the outsider-willing-to-conform-to-be-wanted who looked one way, sounded another.

By 2008, Christopher Hall had no qualms about shit-talking Stabbing Westward’s swan-song album, informing an interviewer that, actually,

The demos to that album were much darker and much heavier...our manager took over the band and talked a couple of the guys in the band into being, like, more pop, like you can make it more pop, more Goo Goo Dolls, and it’ll sell more records and there are guys in the band going, you know, that’s a terrible idea, we just sold half a million records, like on the last album, why would you want to ostracize an entire fanbase of people? You lose your whole core base. I was fighting against it, Walter was against it, and Mark was hellbent against it, and she [the manager] fired him.

The plan didn’t work; it was our lowest selling record. It turned off all of our fans.

I can’t listen to that record, I was pretty embarrassed. And she changed the way we looked and dressed. It was pretty bizarre.”

Apparently Stabbing Westward’s new manager had brought in a guitarist who was “like a very Oasis, kind of Brit-Pop guitar player (Derrek Hawkins)…and then she brought in the producer [from] Suede.” The manager locked Hall out of the studio after Stabbing Westward had recorded their tracks, and Hawkins laid down his terribly corny guitar fills on “Are You Happy,” swinging guitars on “Breathe You In,” all these guitar tracks smothering the band’s original intent.

Hall said that “‘The Only Thing’ was a love song to the girl who is now my wife, which is, like, one of the most popular songs at weddings now…I’ve had a hundred people ask permission to play it at their wedding and stuff,” but that’s a patently absurd claim since “The Only Thing” isn’t the best choice for a wedding song off the self-titled album—it’s clearly “I Still Remember”—the sound is more romantic, the emotions more romantic. But maybe I’m only saying that because I’m still fixated on how Stabbing Westward changed their sound and wrote that love song about memory and transcending space and time but no one bought it so they broke up, and my internet boyfriend and I had broken up but couldn’t restrain ourselves from emailed grasps at the people we had thought we were, the relevance we thought we’d always have.

My internet boyfriend! My internet ex-boyfriend! It was twenty years ago! But Stabbing Westward reunited; they will be out on a twentieth-anniversary tour for Darkest Days this fall, playing the album in its entirety. I could replace the memory of the “Drowning-Desperate Now-Goodbye” suite, supplanting the death throes I had refused to hear with an acknowledgment that sometimes, emotion overrides logic. Yet here I am, no tickets downloaded onto my phone, with an offer of contact information for a brother of a Stabbing Westward bandmate as I write this essay, and I continue to find reasons not to email him.

It is the sort of connection I thought I would have died for—someone who lived in the skin under the black velvet shirt my hands never penetrated—yet I still can’t bring myself to trade fantasy for facts, to risk a reconstruction of the band who dominated a relationship I can barely release.

Vladheads, I see you shaking a long, bony finger at me. Who the fuck cares? Stabbing Westward never pretended to be goth. They never claimed they were goth. Why are you scrolling through this essay about a band that wasn’t even mallgoth? Industrial, industrial: any fool can tell the difference.

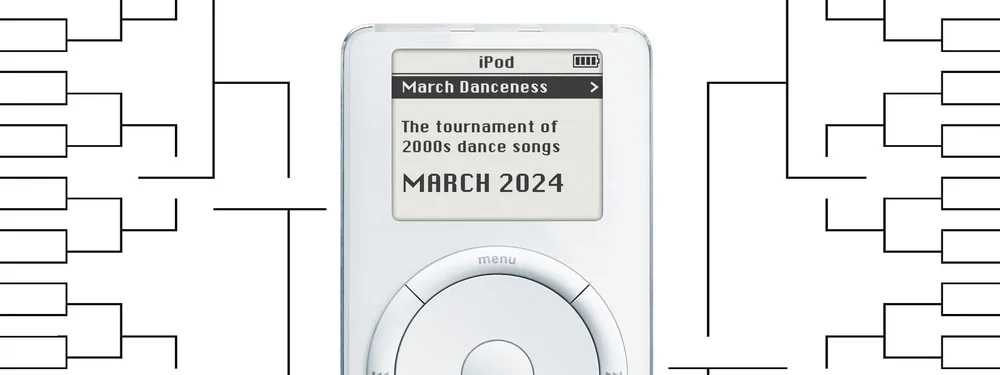

But this fool couldn’t. This fool didn’t know the damn difference until March Vladness released the first 48 tournament selections and I scanned the list, incredulous that I didn’t recognize a single song. How could this be? I had over-argued my teen identity as a Goth Girl for years; I had so much goth cred I had introduced Goth Night to my Midwestern I-state college friends (a “night” which consisted of me dressing them up in black clothing and black lipstick and steering them downtown for ice cream at Whitey’s because I didn’t know what was supposed to happen next).

But I had really only ever known Stabbing Westward, and not even as well as I’d thought: I watched their music videos long after the band was dead, digging into their origins and searching for some sort of evidence they’d once thought they were vaguely goth too.

I still have my pot of dark blue eyeshadow somewhere. I can smear it across my eyelids, set my phone camera on a timer at a selfie-angle, chew my lip ‘til it bleeds. I can lace up my black combat boots and step back into the cesspool of confusion and desire that backwashed off my adolescence; what do I have to do? It’s an affectation, slipping on fishnet sleeves to recreate an old feeling—it’s not Real—but if you don’t know what you’re looking at, it’s close enough.

Kristine Langley Mahler cannot save you—she can’t even save herself. She is a memoirist experimenting with the truth on the suburban prairie outside Omaha, Nebraska, and her work has been recently published in The Normal School, New Delta Review, Quarter After Eight, The Collagist, Gigantic Sequins, and The Rumpus.